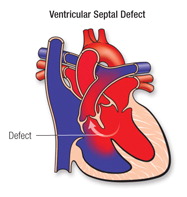

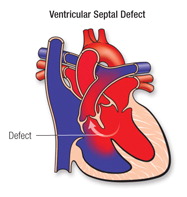

VSD is a hole in the wall separating the two lower chambers of the heart. In normal development, the wall between the chambers closes before the fetus is born, so that by birth, oxygen-rich blood is kept from mixing with the oxygen-poor blood. When the hole does not close, it may cause higher pressure in the heart or reduced oxygen to the body.

What causes it?

In most children, the cause isn’t known. It’s a very common type of heart defect. Some children can have other heart defects along with VSD.

How does it affect the heart?

Normally, the left side of the heart only pumps blood to the body, and the heart’s right side only pumps blood to the lungs. In a child with VSD, blood can travel across the hole from the left pumping chamber (left ventricle) to the right pumping chamber (right ventricle) and out into the lung arteries. If the VSD is large, the extra blood being pumped into the lung arteries makes the heart and lungs work harder and the lungs can become congested.

How does the VSD affect my child?

If the opening is small, it won’t cause symptoms because the heart and lungs don’t have to work harder. The only abnormal finding is a loud murmur (noise heard with a stethoscope).

If the opening is large, the child may breathe faster and harder than normal. Infants may have trouble feeding and growing at a normal rate. Symptoms may not occur until several weeks after birth. High pressure may occur in the blood vessels in the lungs because more blood than normal is being pumped there. Over time this may cause permanent damage to the lung blood vessels.

What can be done about the VSD?

If the opening is small, it won’t make the heart and lungs work harder. Surgery and other treatments may not be needed. Small VSDs often close on their own. There isn’t any medicine or other treatment that will make the VSD get smaller or close any faster than it might do naturally.

If the opening is large, open-heart surgery may be needed to close it and prevent serious problems. Babies with VSD may develop severe symptoms and early repair, within the first few months, is often necessary. The repair may be delayed in other babies. Medicines may be used temporarily to help with symptoms, but they don’t cure the VSD or prevent permanent damage to the lung arteries.

Closing a large VSD by open-heart surgery usually is done in infancy or childhood even in patients with few symptoms, to prevent complications later. Usually a patch of fabric or pericardium (the normal lining around the outside of the heart) is sewn over the VSD to close it completely. Later this patch is covered by the normal heart lining tissue and becomes a permanent part of the heart. Some defects can be sewn closed without a patch. It may be possible to close some VSDs in the cath lab.

If an infant is very ill, or has more than one VSD or a VSD in an unusual location, a temporary operation to relieve symptoms and high pressure in the lungs may be needed. This procedure (pulmonary artery banding) narrows the pulmonary artery to reduce the blood flow to the lungs. When the child is older, an operation is done to remove the band and fix the VSD with open-heart surgery.

What activities can my child do?

If the VSD is small, or if the VSD has been closed with surgery, your child may not need any special precautions regarding physical activity and can participate in normal activities without increased risk.

What will my child need in the future?

Depending on the location of the VSD, your child’s pediatric cardiologist will examine your child periodically to look for uncommon problems, such as a leak in the aortic valve. Rarely, older children with small VSDs may require surgery if they develop a leak in this heart valve. After surgery to close a VSD, a pediatric cardiologist will examine your child regularly. The cardiologist will make sure that the heart is working normally. The long-term outlook is good and usually no medicines or additional surgery are needed.

What about preventing endocarditis?

Ask about your child’s risk of endocarditis. Your child’s cardiologist may recommend that your child receive antibiotics before certain dental procedures for a period of time after VSD repair.

A ventricular septal defect (VSD) is a defect in the septum between the right and left ventricle. The septum is a wall that separates the heart’s left and right sides. Septal defects are sometimes called a “hole” in the heart. It’s the most common congenital heart defect in the newborn; it’s less common in older children and adults because some VSDs close on their own.

What causes it?

In most people, the cause isn’t known but genetic factors may play a role. It’s a very common type of heart defect. Some people can have other heart defects along with VSD.

How does it affect the heart?

Normally, the left side of the heart only pumps blood to the body, and the heart’s right side only pumps blood to the lungs. When a large opening exists between the ventricles, a large amount of oxygen-rich (red) blood from the heart’s left side is forced through the defect into the right side. This blood is pumped back to the lungs, even though it has already been refreshed with oxygen. Unfortunately, this causes the heart to pump more blood. The heart, especially the left atrium and left ventricle, will begin to enlarge from the added work. High blood pressure may occur in the lungs’ blood vessels because more blood is there. Over time, this increased pulmonary hypertension may permanently damage the blood vessel walls. When the defect is small, not much blood crosses the defect from the left to the right and there’s little effect on the heart and lungs.

How does the VSD affect me?

In childhood a large opening may have caused breathing difficulties and therefore, most of these children had surgery to close the defect. Therefore, large VSDs in adults are uncommon, but when they are present, can cause shortness of breath.

Most adults have small VSDs that don’t usually cause symptoms symptoms because the heart and lungs don’t have to work harder. On physical examination, small VSDs produce a loud murmur. Even small VSDs may occasionally be a source of infection called endocarditis.

What if my VSD is very small or closed by itself?

Many children who had a VSD did not need surgery or other treatments, and many of these defects closed on their own. Adults who were told they “had a hole in their heart” that closed on its own usually have no murmur and a normal EKG. If an echocardiogram is performed, it may show an outpouching called a ventricular septal aneurysm in the area where the VSD was located. If the aneurysm isn’t recognized as an expected finding after a VSD has closed, it can lead to unnecessary concern and testing.

If my VSD was closed in childhood, what can I expect?

If the opening was large, it’s likely that open-heart surgery was performed.VSD closure is usually performed by sewing a patch of fabric or pericardium (the normal lining around the outside of the heart) over the VSD to close it completely. The normal heart lining tissue eventually grows to cover this patch and it becomes a permanent part of the heart. Some defects can be sewn closed without a patch. It’s now possible to close some types of VSDs in the catheterization laboratory using a special device that can “plug” the hole and some younger adults may have had this procedure.

Patients with repaired VSDs and normal pulmonary artery pressures have normal lifespans. Late problems are uncommon, but a small number of patients may have problems with the heart valves (aortic or tricuspid) or extra muscle inside the right side of the heart. Anyone who had surgery for a VSD requires a regular check up with a cardiologist who is experienced with adults with congenital heart defects. Medications are rarely needed. In a patient with a large unrepaired VSD, pulmonary hypertension can occur.

What if the defect is still present? Should it be repaired in adulthood?

Usually closure is recommended for small VSDs only if there’s been an episode of endocarditis which is a heart infection that may be due to the VSD, or if the location of the VSD affects the function of one of the heart valves. If the VSD is large, the pressure in the lungs determines whether it can be closed in an adult patient. Those with low lung pressures will benefit from surgery; those with high pressures may or may not.

Problems You May Have

Patients with small VSDs that stay open have a small risk of a heart infection called endocarditis. The aortic valve may develop leakage and should be monitored.

Patients whose VSD has been repaired early in life are unlikely to have any significant long-term problems. If the ventricular septal defect is completely closed without a leak in the patch, the risk of late infection, endocarditis, is minimal. Rarely, abnormal heart rhythms can occur. In some people, the heart muscle may be less able to contract following a VSD repair. If heart failure develops as a result of the heart muscle weakness, diuretics to control fluid accumulation, agents to help the heart pump better and drugs to control blood pressure are often given.

Congenital heart disease (CHD) is the most common congenital disorder in newborns. There are no published data on the occurrence of congenital heart disease in Kerala. However there is general agreement among health workers that it follows a similar pattern all over the world in different geographies. The reported prevalence of CHD at birth ranges from 6 to 13 per 1000 live births. On an average, 8 children are born with congenital heart defects for every 1000 live births in India. Variation is primarily due to the use of different methods to detect CHD (fetal echocardiography versus postnatal referral to a cardiac center). Deriving from the crude birth rate, it…

keep reading

Congenital heart disease (congenital heart defect) is an abnormality in your heart’s structure that you’re born with. Although congenital heart disease is often considered a childhood condition, advances in surgical treatment mean most babies who once died of congenital heart disease survive well into adulthood. While medical advances have improved, many adults with congenital heart disease may not be getting proper follow-up care. If you had a congenital heart defect repaired as an infant, you likely still need care as an adult. Symptoms Symptoms or signs of congenital heart disease may not show up until later in life. They may recur years after you’ve had treatment for a heart defect.…

keep reading

Minimally invasive heart surgery (also called keyhole surgery) is performed through small incisions, sometimes using specialized surgical instruments. The incision used for minimally invasive heart surgery is about 3 to 4 inches instead of the 6- to 8-inch incision required for traditional surgery. The traditional heart surgery procedure Open heart surgery is typically done through a vertical cut placed over the middle of the chest, including full division of the breastbone.While most patients tolerate this well, it can take around 12 weeks or more before the wound is completely healed. This can seriously delay a return to normal activities. These days, it is often possible to avoid such invasive options…

keep reading

about Dr sajan koshy

Pediatric Cardiac Surgeon

Dr Sajan Koshy MS MCh is currently heading the unit of Paediatric & Congenital heart surgery at Aster Medicity. Prior to joining Aster, he was working as senior consultant and head of the department of paediatric cardiac surgery at MIMS Calicut. He started his professional career from alleppey medical college in 1988. He also functioned as a co- convener in first and second symposia on perioperative care of congenital heart disease held in Kochi in the year 2002 and 2004 respectively & as the scientific committee chairman for the national CME of cardio thoracic surgery held at Calicut in September 2007. He has Conducted many lectures in all the districts of North Kerala for the benefit of medical professional bodies to create awareness about congenital heart disease.

read more